Brian: Hello, Andrew. This is the first day of the Austin Film Festival and I’m glad to sit

down with you. I wanted to talk to you about your writing in your career. The first

question I want to ask you is about your origin story, what made you want to be a writer,

and who were some of your favorite writers growing up?

Andrew Kevin Walker: I really focused on screenwriting in college. I knew when I was

a young kid that I wanted to work in the film industry. I remember, I was just talking to

somebody about it because it was Jaws fiftieth anniversary, because it was so

influential for me and it really made me realize what a director does, et cetera. I was

really into film early on and nerding out, reading American Film magazines and stuff in

high school. I went into college studying film at Penn State, I was probably thinking I

wanted to be a director but I really focused on screenwriting. There was an amazing

screen writing teacher that was there at the time, I think he may still be teaching at

Temple, his name is Jeff Rush. It was at Penn State that I focused on writing.

Some my favorite writer’s? William Goldman is probably my favorite screenwriter of all time. My favorite novelist is [William] Somerset Maugham, which is not too surprising, I guess, there’s a couple of Somerset

Maugham references in Se7en. As far as screenwriters go, Waldo Salt and William

Goldman, some of the guys who were writing real classics, you know. My favorite two

movies are Midnight Cowboy and Lawrence In Arabia.

Brian: That covers a lot.

Andrew: That covers the city and the desert I guess (laughs).

Brian: You mentioned Jaws. Obviously, you’re a seventies kid, tell

me about the movies from that time that really shaped you and do you believe the edge

in your screenplay comes from those movies in the seventies?

Andrew: Maybe. It’s a bit of a cliche coming out of my mouth, when I talk about what I

like to call the cinema of discomfort, which are movies where you can experience from

the safety and comfort of the theater experiencing worlds that you would never want to

wander into in real life. Therefore, I call it the cinema of discomfort. It could be anything

from Full Metal Jacket to Taxi Driver. There were so many back in the seventies, so

much of the William Friedkin stuff, Taxi Driver, like I mentioned, Midnight Cowboy,

Dirty Harry is one, which I saw at a younger age than I was probably ready for it. Those are

the kind of movies that were getting made with a little more regularity. The struggle to

make them in the seventies, and any time, was an actual struggle, they weren’t easily

made. There’s a story of Warren Beatty literally getting down on his knees to beg to get

enough money, I’m paraphrasing, to finish Bonnie and Clyde. There were great films

then, there are great films now. Anyone who is neglecting past cinema has a lot to learn

is my point also.

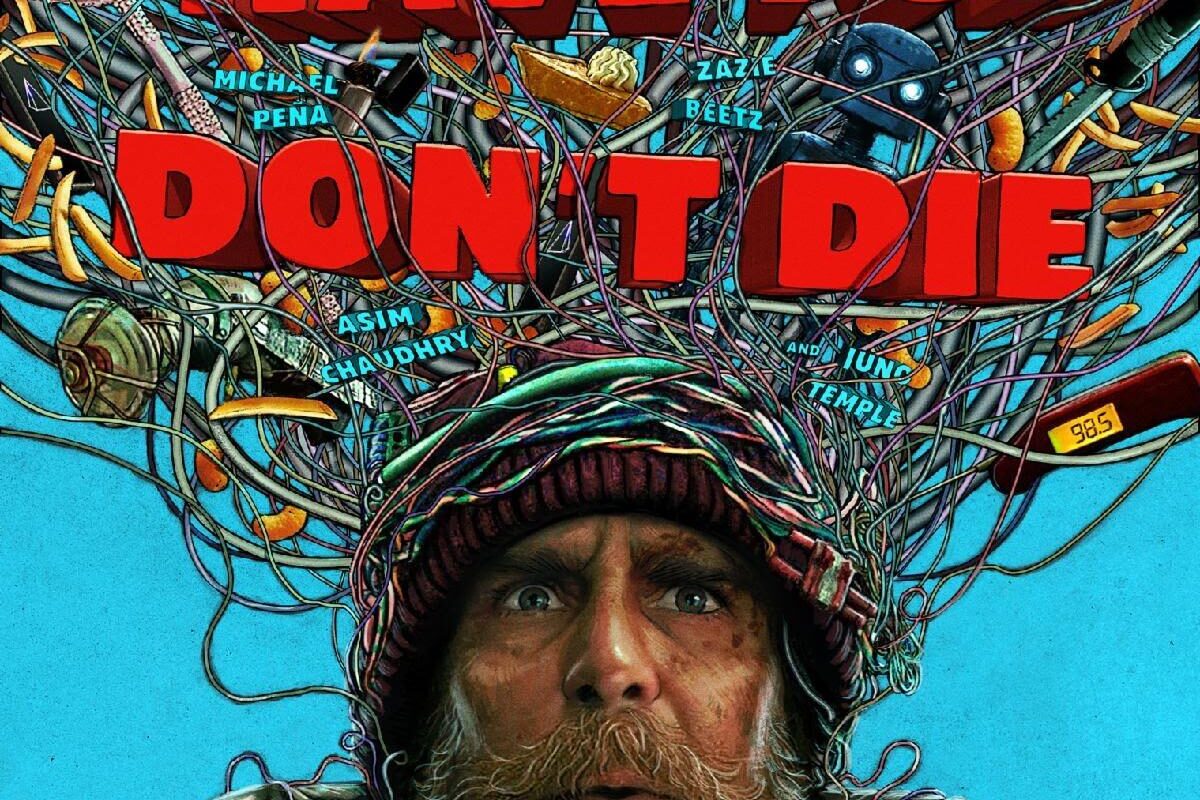

Brian: I’m a big fan of seventies films. So, Se7en turned 30 this year.

Andrew: Yes it did, how is that possible?

Brian: I know, it seems like it was just yesterday. When did you realize that the cultural

reverence of the movie had to come?

Andrew: I wouldn’t really be able to speak to that. I wouldn’t say it’s at all culturally

relevant, other than it’s surprising to me that it’s still around people like it, or even are

still aware of it.

Brian: I think Se7en for me is like “spin the 90’s”, is one of the most quotable

movies. What was your favorite line from the film? And also, do you have a favorite line

that didn’t make it? Like I love “Swat goes before dicks”. That was one of my favorite lines.

Andrew: All the good stuff, as David Koepp likes to point out in a movie, anything that

gets a laugh is usually ad-lib because it’s so of the moment. So a lot of the stuff that

people really love are references to Yoda and stuff, you know. These scripts are up on

andrewkevinwalker.com for free if anyone wants to see the first draft, you can really see

what changed from the page to the screen. But all my favorite lines are usually adlibs,

so they weren’t probably in the script. I think “what’s in the box” was in the script,

thankfully, so I can take credit for that one.

Brian: Which is a great one. You’ve changed the question of ‘what’s in the box?’ forever now.

Andrew: I guess so.

Brian: Speaking of the ending of Se7en, it’s famously uncompromising. I’m curious, how close did it come to the ending being changed? I had read somewhere that the studio had wanted to change it, it was too dark, what made you fight to keep it?

Andrew: Again, the script is out there if you want to see it, it’s very close to the original

ending. Although, there were other scenes that followed that changed. The intention was always to

have that be ending, it changed a lot when Jeremiah Chechik came on to the

project very early on as the director. It was one of my first jobs in Hollywood. I had

written Se7en when I was working at Tower Records in New York City, once it was

optioned and it was assigned to a director, I just rewrote it, kind of dutifully, and he

really changed everything about it, as far as its intention, I would say, especially when it

came to the ending. There was no head in the box in the rewrite for Jeremiah but

[David] Fincher later came along, a short version of the long story, and saved it. They

accidentally sent him the original draft with the head in the box and when he was talking

to executives, this was obviously after Jeremiah Chechik was off the project, Finicher said

“Oh, head in the box, blah, blah, blah.” and they were like “oh, wait-wait-wait, we sent you the

wrong draft.” Then they sent him the Jeremy Chechik draft that I had rewritten for

Jeremiah and Finicher, luckily, said “no, I want to go back to the original.” But everyone,

from Brad [Pitt] to Morgan [Freeman], especially Mike De Luca and Finicher, obviously,

really had to fight, fight, fight to maintain that ending, to be able to test that ending, it’s a

huge credit to Mr. De Luca and everyone at New Line at the time that they would test

this movie, it was tested like a horror movie. In my experience, horror movies often get

split 50/50 down the middle with test audiences and that’s just the nature of Horror. A lot

of times people are walking into a test screening and they have no idea what they’re

about to see. So, you can imagine how people, who had no idea what they’re about to

see, reacted to Se7en. It really is a miracle that it had the ending it has. I think the

reason is kind of still a little bit in the zeitgeist, or people still have awareness of it, that

the ending is true to the story and it’s a surprise. There’s going to be a screening of it

tomorrow and I’m going to ask who here hasn’t seen it. I don’t like to talk about the

ending, there’s plenty of people who haven’t seen it, I still like the idea that someone

could be surprised by it.

Brian: It’s one of the great ending. I love that because I feel like if it didn’t have that ending, the

movie would have lost some of its meaning, because the whole movie feels that

way.

Andrew: The movie is about how sometimes the bad guy wins or evil wins, and it’s

certainly something that feels a little more realistic, but you have to make a choice

whether you keep fighting or not.

Brian: Is there something you’ve written that you’re proud of that didn’t get the attention

that Se7en did, that you think people should give another visit?

Andrew: I mean, any screenwriter has a trail of corpses behind them, meaning scripts

that they wrote that will never see the light of day. I’m very proud of the stuff I’ve worked

on that I’m still fighting to get made. I did write a script called Machinery At Night, where

I used Allen Ginsberg’s poem Howl, almost like a piece of music, in it. We’re trying now

to get that going with Jonas Åkerlund as the director. There’s all kinds of scripts that I’ve

written like Red, White, Black and Blue, which was kind of a seventies cop movie. I did

an adaptation of The Reincarnation of Peter Proud, a remake version of that for Fincher

that I doubt will ever see the light of day. I did a rewrite for Fincher of 20,000 Leagues Under The

Sea. You know, every screenwriter regrets every script that doesn’t get made, I think it’s

the simple answer to that, that’s just the nature of the beast.

Brian: I understand. Your work often blurs the line between noir, horror and psychological

thrillers. How do you define genre when you write?

Andrew: I think Se7en is a horror film, and cop potboiler, but I don’t think you can really call it a murder

mystery. I think genre serves your purpose. Obviously you’re going to say to yourself,

“I’m writing a comedy” or “I’m writing an action-thriller” or whatever, but it doesn’t

really matter. What I would say is figure out what the genre is almost after you’re done

with it, rather than trying to pack something your writing full of conventions that you feel are

required by that genre. Does that make sense?

Brian: Yes, it does. I’m curious, I know you’ve worked both as a solo writer

and a script doctor. I read that you did some touch-ups on The Game and Fight Club

and some other movies. How do you balance your own voice with someone else’s

vision while re-writing?

Andrew: Well, I think that every screenwriter gets rewritten. Every screenwriter in their career

at a certain point is going to rewrite someone or do a new interpretation of something

that someone’s done. It’s just sticky-wicket as they say. One of my rules is, if I’m ever

asked to rewrite a friend, I just won’t do it, no matter how enticing that opportunity may

be. Even if a fellow screenwriter that you know and care about says, “oh, go ahead, I’m

over that project.” It’s still painful if you read something that’s been rewritten by

somebody and reinterpreted by them. So, that’s one of my rules for that reason, to steer

clear of the emotion of traipsing through someone else’s work. For the most part, you

just have to realize, going into something, if you’re working with a writer-director, that

you’re going to get rewritten. It’s just the nature of that director, if they’re a hyphen in it,

they’re going to rewrite you. When it comes to rewriting other people’s stuff, I just try to

fulfill the director’s vision and that’s because that’s the guiding light of any project,

whether it’s an original, an adaptation, or something that you’re rewriting. Once you

have a director, you’re really only writing for the director. That’s the only way to avoid

worrying about the kind of cascade of notes that come from other sources like the studio

or the producers. It really only matters once the director’s on fulfilling that person’s

intention.

Brian: You worked with Fincher a lot, you worked with [Tim] Burton. A lot of

screenwriters write with the same directors. You think that’s law but it’s just a comfort level.

Andrew: Somebody like Eric Roth has a relationship with Michael Mann. It’s natural

that they would. There’s a kismet, there’s this synchronicity. Fincher and I do have a

tendency to think on the same wavelength often. I’ve just been blessed that someone

that incredibly talented as Fincher is forgiving of my stupid writing. If you’re lucky

enough to work with Fincher once, you’re going to want to work with him twice or three

or four times, it’s a blessing. So, there’s a shorthand that comes with working for the same person. There’s the satisfaction of knowing that your material is in the hands of someone who’s going to treat it respectfully and actually hear you out and respect your opinion.

Brian: So, I’m curious. Do you think screenwriting has changed for better or for worse

since you first came to Hollywood?

Andrew: You know, I don’t know. Everything’s different and in five years, ten years, it’ll

be different again. The one thing about screenwriting is that it’s one of the disciplines

related to a film where you can actually sit down and without a big budget; so it’s the

same thing in my opinion. You just have to write a script, and then try and either set it

up, make it, or sell it. And then, you have to write another one, and you have to write

another, write another one. Not just for the sake of trying to get stuff made, which is so

hard and has always been hard to get things made. My career isn’t exactly chock full of

a yearly movie getting made in any way shape or form, but also you’re rewriting and

writing the next one and writing the next one, because you just want to get better at it.

It’s the whole 10,000 hours, is that how many hours it is? I think screenwriting is

probably one of the things that’s changed the least. In my opinion, I will quibble with

those who punctuate only one space after, you know, a period or whatever, because it

drives me insane. That’s the biggest change I’ve seen in screenwriting, it drives me

nuts. (Both laugh) It’s just the youngsters!

Brian: So, speaking of youngsters, what advice would you give writers trying to tell dark

and uncomfortable stories and still get emotional?

Andrew: Use two spaces! Use two spaces. You want to write dark stories? Just write

them. It’s the same thing and it will be the same. I feel like I’m kind of a screenwriter

advice machine that just blabs the same kind of cliches over and over to anyone.

Whoever’s here this weekend in Austin will hear me saying this stuff, but my advice is

just, it’s the same thing every time, write the movie that you want to see. And that’s

making a calculated choice to write something they’re not interested in but that you think

is commercial. It seems a very obvious mistake, but it’s a mistake that I think a lot of people perhaps make. And you can’t put all your eggs in one basket, as that cliche goes. You can write the darkest script you’ve ever written and just get it out there and then work on the next one and the next one. You can’t expect that the first script is necessarily going to land and get made, et cetera, hopefully it will. That’s my advice. I

didn’t sit down and write Se7en and think, “Oh my God, this movie with this ending is

going to be a huge success.” I was more writing this thing that I hoped would get a

chance to be made. It was trying to squeeze every bit of potential out of the concept of

the seven deadly sins murders and that’s what you’re doing, you’re servicing the story,

not an intention to be getting it made. So you just write it as dark or as light as you want.

I mean, happy endings are perfectly great for certain movies too, and you’re just trying

to write what’s appropriate with the movie that you want to see.

Brian: I love that advice. So, as a writer, you’ve been doing this for a while, obviously.

Andrew: (Laughs) A long time.

Brian: Is there still anything that scares you?

Andrew: About writing? All the time. I’m miserable. My other cliche is, if you’re enjoying

writing, you’re doing it wrong. I still lose sleep over scripts. What scares me is getting

paid to write something and then having to go write. That terrifies me. I have some

coping mechanisms, one of which is extensive outlining and not wanting or accepting

trying to get a job before I have a really specific outline that I could walk through with the

potential employers. So, the same things, at my advanced age that terrify me are things

that terrified me when I got the job to write a version of Batman Vs. Superman for

Warner Brothers and I lost. I started to really experience insomnia after that. There’s a

lot of stress in writing for pay, obviously, and feeling like you want to be able to deliver.

It’s another thing you’ll hear me say very often, my screenwriting motto is, I wouldn’t

know if you would say it’s a motto, but my credo is, “your disappointment destroys me.” It

really has to do with trying to be creative and then handing it to people and then seeing

the frown on their faces. Especially with someone like Fincher. There’s a trust there where you can hand stuff back and forth and know that we can enter into a rewriting process where he’s forgiving. Because of the rapidity of the process, if that’s a word, he’s getting the first draft stuff, he’s getting very raw stuff because I don’t want to head it down the wrong path. So, it goes back and forth in a way that’s incredibly helpful to try and get where we want it to be but, also, continues to move forward, even as I make

changes to stuff that I’ve written.

Brian: Speaking of screenplays, looking back, what’s a script of yours that didn’t get

made, but you still believe in deeply?

Andrew: Every single one of them. I wrote a script called Old Man Johnson. It’s about a

young guy, in his early twenties, who apparently thinks he’s very old. I mentioned

Machinery at Night, which is set during the beat generation in the fifties, it’s kind of semi

[Alfred] Hitchcock, an ode to the beat; and we’re still trying to get it made. I wrote that

more than 15 years ago. I would love to see any of these resurrected. I would love to

see Disney pick up the script that we just did a re-write on it. Do 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and fulfill Fincher’s version of it, have him direct it because it’s an incredible

story that he wanted to tell his version of. The Reincarnation of Peter Proud was a lot

of fun because you could kind of be true to the original movie, but also, pull some more

stuff out of the book and so on and so on. I did an adaptation of Somerset Maugham’s Of

Human Bondage for Turner Pictures years and years ago that I would love to see. So,

they’re never dead to me. I can only put up on my website the screenplays that I

“publish onto my website” which are downloadable. Like, I said again, worth every

penny of free. I don’t put up ones, obviously, that aren’t produced. Some of them are

floating around out there. When I did a version of Silver Surfer for Fox, if I tried to make

a list of all the scripts I made, it’s a list that’ll never get made. It’s a long list. As any

writer, I think they’re worth, whatever expression you want to use, worth their salt or

worth their weight. Every script that doesn’t get made, they’ve cried tears over. So, as

long as those writers fulfilled their obligation, they should be proud of that script and

wishing that it would get made. There’s many scripts that are out there that have produced some of the screenwriter’s best work ever and that’s just the way it goes. I’ve

read David Koepp scripts that were fantastic that haven’t gotten made.

Brian: I have one more question for you, this is an easy one. If you can adapt a

Grimm’s fairytale into a film, which one would you pick?

Andrew: I don’t know. I’m going to show my ignorance of Grimm’s fairytales but not

knowing any. Let’s look them up quickly on my phone.

Brian: That was a question of a friend of mine that he wanted to ask you.

Andrew: Love that. Well, let’s see the title list. Cinderella is Grimms? This is an

interesting one, The Wolf and The Seven Young Kids, what the hell is that? It wouldn’t

be Snow White. It might be Hansel and Gretel, though. Although, I don’t know if that

would be interesting. Well, Puss ‘N Boots has done, there’s other notable titles, The

Elves, The Mouse, the Bird, and the Sausage. I really don’t know. Maybe Rapunzel.

That seems like it would be interesting. Little Red Riding Hood, which has been done,

obviously, as a werewolf movie in the early eighties. It’s funny, though, because of

Sleepy Hollow, et cetera, et cetera. I think certain pieces of literature and lore that

haven’t been mined by people or adapted for popular entertainment. I’m not going to sit

here and name any of the ones I’m thinking of, because maybe I’ll get around to doing it

one day. It was funny, I guess, along the lines of what you’re asking is simply, you

know, when Kevin Yagher, many, many years ago – Kevin is an incredibly talented

director and makeup artist. He created The Crypt Keeper and Chucky. When Kevin

Yagher came to me many years ago and said he was interested in doing a version of

Sleep Hollow, we did it. We figured it out. It took a long time to figure out a three act

structure kind of version of that story. We set it up and there were people who were kind

of hitting their head and going, “God damn, why didn’t we think of doing Sleepy

Hollow?” If people actually paid a little more attention to that list of Grimm’s Fairytales,

especially some of the ones that I’m looking at down on my phone, or ones that are more obscure. There’s a whole bunch of undiscovered stories that would be worth exploring.

Brian: Thank you for your time.